11.10.03

Webshots Community - CREATING POLITICAL ART

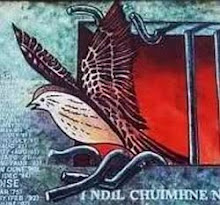

Check out what happened to the new Belfast mural under cover of darkness.

Check out what happened to the new Belfast mural under cover of darkness.

SATURDAY 11/10/2003 08:45:21 UTV

SF: Ministers set to revive elections

Ulster Unionist leader David Trimble and Sinn Fein president Gerry Adams were preparing today for arguably their most important face-to-face meeting in the current efforts to revive devolution. By: Press Association

With speculation hardening that the British government may announce next week plans for a November or December Assembly election, the two leaders were expected to meet in Belfast for discussions which could map out efforts to restore devolution.

As parties in Northern Ireland prepared their rank-and-file for an Assembly poll to begin within days, Sinn Fein claimed it believed the British government was extremely close to announcing the election would go ahead.

A party source said: ``We believe the argument for an election has been won.

``Parties expect the government to announce a polling date.

``However, given the bitter experience of the Spring, we are not counting our chickens.``

Earlier this year, British Prime Minister Tony Blair pulled plans for a Stormont election four days into the campaign.

He did so because he was dissatisfied with public assurances from the IRA and Sinn Fein president Gerry Adams that republicans would not do anything inconsistent with the Good Friday Agreement.

Devolution in Northern Ireland has been suspended since October last year when the power-sharing executive threatened to collapse over allegations of IRA spying.

Northern Ireland has for the past year been ruled by a team of Northern Ireland Office ministers from Westminster.

Republicans have resisted pressure for the IRA to make an historic declaration that it is ending all recruiting, training, targeting, intelligence gathering, weapons procurement and involvement in all violence.

Over the past week the belief among most participants is that the Republican Movement will fall short again.

However, there is a belief that the IRA or Sinn Fein president Gerry Adams could go further than before in trying to reassure unionists.

There has also been a belief that the IRA is planning a more transparent act of arms decommissioning in a bid to create the conditions for an election.

Sinn Fein leaders Mr Adams and Martin McGuinness were in Downing Street yesterday to meet the Prime Minister and his chief of staff Jonathan Powell.

US president George W Bush`s special advisor on Northern Ireland Richard Haass is also due to travel to the province on Monday for two days of talks with Northern Ireland parties.

If an Assembly election takes place before Christmas, talks insiders believe the most likely date would be November 13, which would mean that the government would have to declare it before Thursday.

Two other dates have also been considered - November 27 and December 4.

Participants in the negotiations were also placing great emphasis on a proposed photocall tomorrow involving members of a new monitoring body which would scrutinise paramilitary cease-fires in Northern Ireland and the implementation of the Good Friday Agreement.

With the head of the Independent International Commission on decommissioning, General John de Chastelain also in Belfast, a source said: ``All the various elements appear to be there for some choreography in the run up to an election.

``We still have to see if all the moves fall into place.``

SF: Ministers set to revive elections

Ulster Unionist leader David Trimble and Sinn Fein president Gerry Adams were preparing today for arguably their most important face-to-face meeting in the current efforts to revive devolution. By: Press Association

With speculation hardening that the British government may announce next week plans for a November or December Assembly election, the two leaders were expected to meet in Belfast for discussions which could map out efforts to restore devolution.

As parties in Northern Ireland prepared their rank-and-file for an Assembly poll to begin within days, Sinn Fein claimed it believed the British government was extremely close to announcing the election would go ahead.

A party source said: ``We believe the argument for an election has been won.

``Parties expect the government to announce a polling date.

``However, given the bitter experience of the Spring, we are not counting our chickens.``

Earlier this year, British Prime Minister Tony Blair pulled plans for a Stormont election four days into the campaign.

He did so because he was dissatisfied with public assurances from the IRA and Sinn Fein president Gerry Adams that republicans would not do anything inconsistent with the Good Friday Agreement.

Devolution in Northern Ireland has been suspended since October last year when the power-sharing executive threatened to collapse over allegations of IRA spying.

Northern Ireland has for the past year been ruled by a team of Northern Ireland Office ministers from Westminster.

Republicans have resisted pressure for the IRA to make an historic declaration that it is ending all recruiting, training, targeting, intelligence gathering, weapons procurement and involvement in all violence.

Over the past week the belief among most participants is that the Republican Movement will fall short again.

However, there is a belief that the IRA or Sinn Fein president Gerry Adams could go further than before in trying to reassure unionists.

There has also been a belief that the IRA is planning a more transparent act of arms decommissioning in a bid to create the conditions for an election.

Sinn Fein leaders Mr Adams and Martin McGuinness were in Downing Street yesterday to meet the Prime Minister and his chief of staff Jonathan Powell.

US president George W Bush`s special advisor on Northern Ireland Richard Haass is also due to travel to the province on Monday for two days of talks with Northern Ireland parties.

If an Assembly election takes place before Christmas, talks insiders believe the most likely date would be November 13, which would mean that the government would have to declare it before Thursday.

Two other dates have also been considered - November 27 and December 4.

Participants in the negotiations were also placing great emphasis on a proposed photocall tomorrow involving members of a new monitoring body which would scrutinise paramilitary cease-fires in Northern Ireland and the implementation of the Good Friday Agreement.

With the head of the Independent International Commission on decommissioning, General John de Chastelain also in Belfast, a source said: ``All the various elements appear to be there for some choreography in the run up to an election.

``We still have to see if all the moves fall into place.``

ic NorthernIreland - Bombings Blamed For Epidemic Of Deafness

Bombings Blamed For Epidemic Of Deafness Oct 10 2003

By Sandra Murphy Health Correspondent

THE deadly noise of bombs exploding and guns firing during the Troubles was blamed for the silent epidemic sweeping Northern Ireland, a leading Ulster charity said yesterday.

Bombings Blamed For Epidemic Of Deafness Oct 10 2003

By Sandra Murphy Health Correspondent

THE deadly noise of bombs exploding and guns firing during the Troubles was blamed for the silent epidemic sweeping Northern Ireland, a leading Ulster charity said yesterday.

9.10.03

IrelandClick.com

Escape from the Crum

----------------------------------

From the grisly past that hangs over the walls of Crumlin Road Jail like a winter fog to a future that has yet to be decided – Crumlin Road prison has had its fair share of dramas.

Enough to script a dozen Hollywood blockbusters, except this is not the work of the scriptwriter – the experiences of the men both on remand and interned in the prison during the present phase of the North’s conflict are very real.

Every man has a story to tell, each one fascinating, heartbreaking, humorous, horrendous, awe-inspiring and infuriating in its own very unique and personal way.

Having witnessed at first hand the living conditions inside the ageing Victorian prison, listening to the former prisoners’ stories has taken on a new significance.

Republican Terence ‘Cleaky’ Clarke, who later died of cancer, described the Crum as, “the dirtiest prison in Europe” adding, “The Crum’s so bad it would put you off going to jail.”

On close inspection I have to agree with him. The jail was built in such a way that very little natural light gets through to the main building.

The sun never shines in Crumlin Road jail.

Narrow corridors, with cells so small that the feeling of claustrophobia is intense, protrude from the centre circle. You can stand in a cell and touch both facing walls – but during the height of the troubles the jail was so over-crowded that the men were doubled up two and sometimes three to a cell.

Each of the four wings – A,B,C and D – is more or less identical apart from being painted in slightly different insipid shades of paint. The three-tier landings are divided by what is known as anti-suicide wire to stop anyone jumping – or being pushed – from the top tier to the concrete floor below.

The prison hospital, a slightly later addition, opened in 1898, is perhaps one of the vilest places I have ever set foot in. More of an asylum than a place where you could expect to receive any type of care or attention.

Over the years the hospital was home to some of the conflict’s most famous prisoners. Tom Williams spent time there in the 40s before his execution and his remains were buried at the rear of the hospital building.

The ‘Padded Cell’, a place where prisoners deemed to be ‘a danger to themselves’ were kept, is still there, albeit in a dilapidated state. For anyone like myself who’s not all that comfortable with small spaces, this is probably one of the worst places I can ever imagine being locked in. The cell is absolutely tiny and completely lined in leather-type fabric with only a tiny slit at roof level for light.

A dead bird lies on the floor of one of the hospital cells, a cupboard in a former medics room contains lice lotion and ointment for scabies – essential tools of the hospital doctor’s trade.

Veteran republican Martin Meehan is just one of the prisoners whose time in Crumlin Road jail is now a part of history and folklore.

The 1971-72 period of internment became noted for the number of successful escapes from the Crum. This was a source of great anger and embarrassment for the then unionist Stormont government.

For the republican internees, of course, this had the opposite effect and morale on the wings was at an all-time high.

Just weeks after the ‘Crumlin Kangaroo’ escape, when nine republican prisoners went over the wall on rope ladders, Martin Meehan, Tony Doherty and Hugh McCann also made a successful bid for freedom.

The escape was the final straw for then Prime Minister Brian Faulkner. Security at the jail had been tightened after the first escape and unionists were reassured that the jail was infallible.

Martin Meehan spent several periods of imprisonment in Crumlin Road during the early Troubles. He recalls: “For republicans, it was our duty to escape.

“Republican prisoners were always plotting new ways to escape, and as well as the successful escapes there were numerous attempted escape plans hatched.

“I was first sent to Crumlin Road Jail in 1969 following the Ardoyne Pogroms. I was sentenced to two months for orchestrating a riot.

“You did your time hard. We wore brown suits with a yellow star on the arm, it was like a concentration camp and it was hard labour. When I was released I swore I would never set foot inside a jail again. I lived to eat those words.

“In 1971 I was remanded in the Crum on a trumped-up weapons charge and planned an escape with my cellmate. He wasn’t a republican but a radical student who was arrested for causing disturbances at some student demonstration. We sawed through the bars on our windows.

“Just before the date we planned to escape Billy McKee came to me and said, you can beat this charge and you are mad to escape. My cellmate went as planned and got away, that was June 10, 1971.

“I went to court on June 29 and sure enough I did beat the charge, not that it did me much good as by November 9 I was interned and back inside Crumlin Road Jail.”

Martin Meehan was interned with Tony Doherty. The two were arrested by the Green Howards and taken to Palace Barracks, where they were beaten and tortured to within an inch of their lives. When Martin Meehan was eventually transferred to Crumlin Road Jail he had 47 stitches in his head.

“I can remember very little about being taken to the Crum, I was totally out of it. We had been given a serious beating. They carried me in laughing and joking. They had put a British army uniform on me, the blood was dripping from my face.

“I remember a screw called William Wilson tried to help me. He told the British army and the RUC to stand back and helped me to the bath.

“He was killed by the IRA in 1979 as he walked from the Crum to the Royal Ancient Order of Buffaloes Club in Century Street. His son went on to become a governor in Long Kesh.”

By December a plan to escape had already been hatched.

Martin remembers it all clearly: “Just after the so-called Kangaroo escape, security at the jail was supposed to be at its height. It was just the second day that we were allowed back on to the football pitch that we escaped.

“The three of us covered ourselves in butter to protect us from the water and during half-time climbed down a manhole. It was a Thursday afternoon and the screws got paid so they were more interested in counting their money than counting heads – they never even noticed we were gone.

“We stayed down there up to our necks in freezing water for six hours. We had made a rope out of sheets with a hook made from the leg of a chair with more sheets wrapped around it so it wouldn’t clink when it hit the wall. By this time a thick fog had fallen.

“I remember we thought there was a Brit with a gun pointing at us through the fog, it turned out to be a cement mixer with a brush pole sticking out.

“We got to the wall and tried to climb up the rope, but we were covered in butter, and kept slipping back down again.

“When we eventually got over the wall there was an old green Avenger car waiting for us in Cliftonpark Avenue with the keys under the mat. But because it was winter the car wouldn’t start. After 10 minutes we got it going and drove down Agnes Street and through the Shankill on to the Falls to a house in O’Donnell Street.

“From there we were taken to another house. I remember the man of the house gave me a pair of shoes to put on. I was to walk to a house in Beechmount and on the way the sole fell off the shoes.

“The escape was a source of great embarrassment for the government at the time. Ian Paisley demanded an inquiry.

“You see, the prison authorities only realised we had escaped after the British army phoned to tell them that people were lighting bonfires in Ardoyne because Meehan and Doherty had escaped.

“That was at about eight in the evening, they weren’t able to do a head count until 9.30 – that was when they discovered we were missing.

“My cellmate at the time, Tommy Muldoon, told me when they came in to search the cell they lifted the piss pot and looked underneath.”

When Martin Meehan was finally recaptured and charged with unlawful escape from Crumlin Road Jail he managed to turn the historic escape into a landmark court case.

He had initially been arrested and interned by the British Army, but the Special Powers Act at the time stated that only the RUC had the authority to charge anyone. Martin Meehan argued in court that his arrest was unlawful, therefore his escape was lawful.

Justice McGonagle conceded the argument and Martin Meehan was released.

“I had no defence lawyers and argued my own case. The judgement was unprecedented and within two days the government rushed through emergency legislation to prevent the other detainees from using the loophole.

“In fact I was awarded £800 compensation for being held illegally. So not only did I escape but I also set a precedent and was compensated into the bargain, not a bad day’s work!”

Falls Road republican Fra McCann’s memories of the imposing Victorian jail are different but no less vivid.

Along with three other republicans – Gerard Murray, Jimmy Duffy and Joe Maguire – Fra was on the blanket protest in Crumlin Road Jail for 16 months.

The four men became known as the ‘Forgotten Blanketmen.’

At the time, what were termed short-term prisoners – those sentenced to less than four years – were left to serve out their sentence in Crumlin Road Jail.

After the removal of Special Category Status, the four men were ordered to put on a prison uniform and conform – make themselves available for prison work. The four refused and joined the blanket protest.

They went on to endure appalling treatment. In fact so much so that the ‘number one diet’ issued to all the men as punishment for not conforming was deemed illegal by the European Court of Human Rights.

Without the camaraderie the other blanket men had within the H-Blocks, Fra and his colleagues found the going tough. “The isolation was one of the worst parts of our time in the Crum – when we were moved to the Kesh it was almost a relief.

“The four of us were kept in solitary, an empty cell between us so we couldn’t talk to each other. Billy Moore and Basher Bates – the Shankill Butchers – were our orderlies.

“Every 14 days we were given three days punishment for not conforming. They would come in to your cell and remove your bed and blankets and leave you naked in the freezing cell for 12 hours.

“You were also issued with what was called the number one diet – black tea and bread in the morning, strained soup at lunch, and black tea and bread for dinner.

“It was a severe regime, but to put on a prison uniform would have been unthinkable.

“A screw once said to a blanketman, ‘I wouldn’t live like you for a million pounds.’ The blanketman replied, ‘Neither would I.’

“That sort of sums it up.”

• Don’t miss Thursday’s Andersonstown News for the conclusion of our three-part series on the Crum.

Journalist:: Allison Morris

Escape from the Crum

----------------------------------

From the grisly past that hangs over the walls of Crumlin Road Jail like a winter fog to a future that has yet to be decided – Crumlin Road prison has had its fair share of dramas.

Enough to script a dozen Hollywood blockbusters, except this is not the work of the scriptwriter – the experiences of the men both on remand and interned in the prison during the present phase of the North’s conflict are very real.

Every man has a story to tell, each one fascinating, heartbreaking, humorous, horrendous, awe-inspiring and infuriating in its own very unique and personal way.

Having witnessed at first hand the living conditions inside the ageing Victorian prison, listening to the former prisoners’ stories has taken on a new significance.

Republican Terence ‘Cleaky’ Clarke, who later died of cancer, described the Crum as, “the dirtiest prison in Europe” adding, “The Crum’s so bad it would put you off going to jail.”

On close inspection I have to agree with him. The jail was built in such a way that very little natural light gets through to the main building.

The sun never shines in Crumlin Road jail.

Narrow corridors, with cells so small that the feeling of claustrophobia is intense, protrude from the centre circle. You can stand in a cell and touch both facing walls – but during the height of the troubles the jail was so over-crowded that the men were doubled up two and sometimes three to a cell.

Each of the four wings – A,B,C and D – is more or less identical apart from being painted in slightly different insipid shades of paint. The three-tier landings are divided by what is known as anti-suicide wire to stop anyone jumping – or being pushed – from the top tier to the concrete floor below.

The prison hospital, a slightly later addition, opened in 1898, is perhaps one of the vilest places I have ever set foot in. More of an asylum than a place where you could expect to receive any type of care or attention.

Over the years the hospital was home to some of the conflict’s most famous prisoners. Tom Williams spent time there in the 40s before his execution and his remains were buried at the rear of the hospital building.

The ‘Padded Cell’, a place where prisoners deemed to be ‘a danger to themselves’ were kept, is still there, albeit in a dilapidated state. For anyone like myself who’s not all that comfortable with small spaces, this is probably one of the worst places I can ever imagine being locked in. The cell is absolutely tiny and completely lined in leather-type fabric with only a tiny slit at roof level for light.

A dead bird lies on the floor of one of the hospital cells, a cupboard in a former medics room contains lice lotion and ointment for scabies – essential tools of the hospital doctor’s trade.

Veteran republican Martin Meehan is just one of the prisoners whose time in Crumlin Road jail is now a part of history and folklore.

The 1971-72 period of internment became noted for the number of successful escapes from the Crum. This was a source of great anger and embarrassment for the then unionist Stormont government.

For the republican internees, of course, this had the opposite effect and morale on the wings was at an all-time high.

Just weeks after the ‘Crumlin Kangaroo’ escape, when nine republican prisoners went over the wall on rope ladders, Martin Meehan, Tony Doherty and Hugh McCann also made a successful bid for freedom.

The escape was the final straw for then Prime Minister Brian Faulkner. Security at the jail had been tightened after the first escape and unionists were reassured that the jail was infallible.

Martin Meehan spent several periods of imprisonment in Crumlin Road during the early Troubles. He recalls: “For republicans, it was our duty to escape.

“Republican prisoners were always plotting new ways to escape, and as well as the successful escapes there were numerous attempted escape plans hatched.

“I was first sent to Crumlin Road Jail in 1969 following the Ardoyne Pogroms. I was sentenced to two months for orchestrating a riot.

“You did your time hard. We wore brown suits with a yellow star on the arm, it was like a concentration camp and it was hard labour. When I was released I swore I would never set foot inside a jail again. I lived to eat those words.

“In 1971 I was remanded in the Crum on a trumped-up weapons charge and planned an escape with my cellmate. He wasn’t a republican but a radical student who was arrested for causing disturbances at some student demonstration. We sawed through the bars on our windows.

“Just before the date we planned to escape Billy McKee came to me and said, you can beat this charge and you are mad to escape. My cellmate went as planned and got away, that was June 10, 1971.

“I went to court on June 29 and sure enough I did beat the charge, not that it did me much good as by November 9 I was interned and back inside Crumlin Road Jail.”

Martin Meehan was interned with Tony Doherty. The two were arrested by the Green Howards and taken to Palace Barracks, where they were beaten and tortured to within an inch of their lives. When Martin Meehan was eventually transferred to Crumlin Road Jail he had 47 stitches in his head.

“I can remember very little about being taken to the Crum, I was totally out of it. We had been given a serious beating. They carried me in laughing and joking. They had put a British army uniform on me, the blood was dripping from my face.

“I remember a screw called William Wilson tried to help me. He told the British army and the RUC to stand back and helped me to the bath.

“He was killed by the IRA in 1979 as he walked from the Crum to the Royal Ancient Order of Buffaloes Club in Century Street. His son went on to become a governor in Long Kesh.”

By December a plan to escape had already been hatched.

Martin remembers it all clearly: “Just after the so-called Kangaroo escape, security at the jail was supposed to be at its height. It was just the second day that we were allowed back on to the football pitch that we escaped.

“The three of us covered ourselves in butter to protect us from the water and during half-time climbed down a manhole. It was a Thursday afternoon and the screws got paid so they were more interested in counting their money than counting heads – they never even noticed we were gone.

“We stayed down there up to our necks in freezing water for six hours. We had made a rope out of sheets with a hook made from the leg of a chair with more sheets wrapped around it so it wouldn’t clink when it hit the wall. By this time a thick fog had fallen.

“I remember we thought there was a Brit with a gun pointing at us through the fog, it turned out to be a cement mixer with a brush pole sticking out.

“We got to the wall and tried to climb up the rope, but we were covered in butter, and kept slipping back down again.

“When we eventually got over the wall there was an old green Avenger car waiting for us in Cliftonpark Avenue with the keys under the mat. But because it was winter the car wouldn’t start. After 10 minutes we got it going and drove down Agnes Street and through the Shankill on to the Falls to a house in O’Donnell Street.

“From there we were taken to another house. I remember the man of the house gave me a pair of shoes to put on. I was to walk to a house in Beechmount and on the way the sole fell off the shoes.

“The escape was a source of great embarrassment for the government at the time. Ian Paisley demanded an inquiry.

“You see, the prison authorities only realised we had escaped after the British army phoned to tell them that people were lighting bonfires in Ardoyne because Meehan and Doherty had escaped.

“That was at about eight in the evening, they weren’t able to do a head count until 9.30 – that was when they discovered we were missing.

“My cellmate at the time, Tommy Muldoon, told me when they came in to search the cell they lifted the piss pot and looked underneath.”

When Martin Meehan was finally recaptured and charged with unlawful escape from Crumlin Road Jail he managed to turn the historic escape into a landmark court case.

He had initially been arrested and interned by the British Army, but the Special Powers Act at the time stated that only the RUC had the authority to charge anyone. Martin Meehan argued in court that his arrest was unlawful, therefore his escape was lawful.

Justice McGonagle conceded the argument and Martin Meehan was released.

“I had no defence lawyers and argued my own case. The judgement was unprecedented and within two days the government rushed through emergency legislation to prevent the other detainees from using the loophole.

“In fact I was awarded £800 compensation for being held illegally. So not only did I escape but I also set a precedent and was compensated into the bargain, not a bad day’s work!”

Falls Road republican Fra McCann’s memories of the imposing Victorian jail are different but no less vivid.

Along with three other republicans – Gerard Murray, Jimmy Duffy and Joe Maguire – Fra was on the blanket protest in Crumlin Road Jail for 16 months.

The four men became known as the ‘Forgotten Blanketmen.’

At the time, what were termed short-term prisoners – those sentenced to less than four years – were left to serve out their sentence in Crumlin Road Jail.

After the removal of Special Category Status, the four men were ordered to put on a prison uniform and conform – make themselves available for prison work. The four refused and joined the blanket protest.

They went on to endure appalling treatment. In fact so much so that the ‘number one diet’ issued to all the men as punishment for not conforming was deemed illegal by the European Court of Human Rights.

Without the camaraderie the other blanket men had within the H-Blocks, Fra and his colleagues found the going tough. “The isolation was one of the worst parts of our time in the Crum – when we were moved to the Kesh it was almost a relief.

“The four of us were kept in solitary, an empty cell between us so we couldn’t talk to each other. Billy Moore and Basher Bates – the Shankill Butchers – were our orderlies.

“Every 14 days we were given three days punishment for not conforming. They would come in to your cell and remove your bed and blankets and leave you naked in the freezing cell for 12 hours.

“You were also issued with what was called the number one diet – black tea and bread in the morning, strained soup at lunch, and black tea and bread for dinner.

“It was a severe regime, but to put on a prison uniform would have been unthinkable.

“A screw once said to a blanketman, ‘I wouldn’t live like you for a million pounds.’ The blanketman replied, ‘Neither would I.’

“That sort of sums it up.”

• Don’t miss Thursday’s Andersonstown News for the conclusion of our three-part series on the Crum.

Journalist:: Allison Morris

CAJ condemns PSNI decision to hold back documents from Mallon inquest

------------------------------------------------

The Committee on the Administration of Justice today expressed grave disquiet at the decision of the PSNI and the MOD not to disclose documents to Coroner Roger McLernon.

The decision was announced in a hearing into the cases of Roseanne Mallon and nine other people who were killed either by the army or by loyalists, in circumstances where there is credible evidence of collusion.

To date some (but not all) material has been supplied to the Coroner but it has been redacted.

Three weeks ago the Coroner ordered that the PSNI and the MOD hand over all material in un-redacted form.

Representatives of the PSNI and MOD made clear in correspondence to the Coroner disclosed at Dungannon court house today that the material would not be disclosed.

A spokesperson for CAJ said the decision to ignore the ruling raised serious concerns about the applicability of the rule of law and the extent to which the PSNI takes its duties under the Human Rights Act seriously.

"When the police simply ignore court orders it hardly augurs well for a new dispensation in policing based on respect for human rights."

For further information please contact Paul Mageean or Martin O'Brien at CAJ 028 90961122 or on their respective mobile numbers 07703 564467 and 07802434769.

Journalist:: Seán Mag Uidhir

IrelandClick.com

------------------------------------------------

The Committee on the Administration of Justice today expressed grave disquiet at the decision of the PSNI and the MOD not to disclose documents to Coroner Roger McLernon.

The decision was announced in a hearing into the cases of Roseanne Mallon and nine other people who were killed either by the army or by loyalists, in circumstances where there is credible evidence of collusion.

To date some (but not all) material has been supplied to the Coroner but it has been redacted.

Three weeks ago the Coroner ordered that the PSNI and the MOD hand over all material in un-redacted form.

Representatives of the PSNI and MOD made clear in correspondence to the Coroner disclosed at Dungannon court house today that the material would not be disclosed.

A spokesperson for CAJ said the decision to ignore the ruling raised serious concerns about the applicability of the rule of law and the extent to which the PSNI takes its duties under the Human Rights Act seriously.

"When the police simply ignore court orders it hardly augurs well for a new dispensation in policing based on respect for human rights."

For further information please contact Paul Mageean or Martin O'Brien at CAJ 028 90961122 or on their respective mobile numbers 07703 564467 and 07802434769.

Journalist:: Seán Mag Uidhir

IrelandClick.com

8.10.03

Northern Ireland News

I'll Make A Lot Of Noise If Anyone Interferes Oct 8 2003

By Alan Erwin

THE Government was warned yesterday that it should not interfere with a report into controversial murders involving alleged security force collusion in Northern Ireland and the Republic.

Canadian judge Peter Cory, who revealed that his exhaustive examination of six killings has uncovered new lines of inquiry, also pledged to hold the Government to its commitment to carry out public inquiries in any cases he recommended.

He said that any bid to alter the 500-page dossier would be resisted.

''I have one younger grandson who expresses it very well. He says 'I'm going down to my room and I'm going to kick and scream and turn blue'.

"I don't think I would kick and scream and I don't think I would turn blue but I would make a lot of noise.''

Receiving the reports in London, Northern Ireland Secretary Paul Murphy said that he would consider their contents speedily and carefully.

He said: ''The two governments are determined that, where there are allegations of collusion, the truth should emerge.

"We will consider the reports urgently and undertake to publish them as soon as possible, in line with the terms of reference.''

He paid tribute to the retired Canadian judge, saying he had put in long hours examining each case.

Irish premier Bertie Ahern said that Minister for Justice Michael McDowell will publish the findings, depending on security aspects.

Mr Ahern said: ''We have not yet finalised the arrangements with the British government on when we will get access to their reports and when they will get access to ours but, certainly, we will exchange information once they are examined by the departments.

"They have an interest in ours and we have an interest in the cases that they put forward.''

The retired Canadian Supreme Court Judge has spent the last 14 months investigating each of the cases after being appointed by the authorities in London and Dublin.

The murders include the loyalist assassinations of lawyers Pat Finucane and Rosemary Nelson, the killings of a high court judge and two senior RUC officers by the IRA, and the shooting of jailed terror boss Billy Wright.

Prime Minister Tony Blair is committed to setting up public tribunals similar to the hearing on the Bloody Sunday shootings if Justice Cory believes any are needed.

It could be two months before his findings are published.

The judge said that the six cases agreed by the two governments and political parties during talks on the peace process at Weston Park in Staffordshire in 2001 were based on calling public inquiries if needed.

"To do anything else might be something that was demeaning of the Weston Park agreement,'' Mr Justice Cory said.

"There are other ways and other situations that can take the place of a public inquiry.

"As I understand the agreement and what was done, there's no alternative to a public inquiry and what would be understood as a public inquiry in 2001 in these six cases selected at that time in which a public inquiry was recommended.''

Fears have been expressed that his independence could be compromised as legal chiefs trawl through the document to blank out any names or information relevant to criminal investigations.

The judge said: ''To some extent, the report is going to demonstrate that independence.''

He has worked closely with detectives, including Scotland Yard chief Sir John Stevens' team investigating collusion claims surrounding the 1989 murder of Belfast lawyer Pat Finucane.

The judge also disclosed that his work had uncovered details not previously known to the detectives.

He said: ''I have seen things that, because of the routes followed, are additional to some of the police investigations.

"I have had tremendous cooperation from Sir John Stevens and his team and I like to think I co-operated with him in the same way''.

It is understood that Mr Justice Cory will return to the UK in mid-November to check on any amendments made to his report.

With the document having to pass through parliament and then be printed, the publication date is likely to be early December.

Mr Justice Cory accepted that the attorney generals faced a difficult task in balancing any criminal prosecutions against public inquiries, if any were needed.

"Very often it's extremely difficult to hold both at the same time.

"In other instances, it's not.

"It depends on the situation and the nature of the evidence and direction the public inquiry is taking.

"I have written concerning it in the reports.''

With the allegations refusing to go away, Mr Justice Cory said: '' Sometimes myths and legends grow up.

"It's important they be shown to be false.

"Sometimes, you can only do that with public inquiries and exploring what has happened.

"Collusion is, in effect, conniving with those who committed the murder by turning a blind eye and secretly encouraging.

"If there's to be confidence, there has be public inquiries if there is collusion.''

icNorthernIreland.co.uk

6.10.03

Omagh families demand Dublin hands over informer

Henry McDonald, Ireland editor

Sunday October 5, 2003

The Observer

Families of the Omagh bomb victims challenged the Irish government last night to hand over an informer who is living abroad under a Garda witness protection programme. Relatives of those killed in the biggest atrocity of the Northern Ireland Troubles said the republic must allow detectives investigating the Real IRA murder of 29 men, women and children to interview the informant.

They were 'shocked and dismayed' that the Irish authorities had not informed the PSNI and the families that a key potential witness had been in protective custody abroad for several years.

The Observer knows the identity of the informer, who is from the Finglas area of north Dublin. At the time of the Omagh bomb he stole cars on behalf of the car dealer for the Real IRA. He knew about the plot to transport a large explosive device into Northern Ireland just prior to the massacre on 15 August, 1998. A heroin addict who fed his habit through crime, the thief told his handlers that the Real IRA planned to put a bomb in a northern town days before the blast.

The informer told his Garda contact that the Real IRA was seeking a Vauxhall Cavalier, the model used to transport the bomb to Omagh. The Real IRA asked him to approach a used car dealer in the republic for a Cavalier. When the dealer was unable to do so, the Real IRA used two other criminals, including a northerner known as 'Belfast Jim', to steal a Cavalier in Co Monaghan, 24 hours before the bombing. None of this intelligence was sent to the RUC.

'Bells should have started ringing the moment the Vauxhall was stolen, given the information the car thief had passed on to his handlers,' one Garda officer admitted yesterday.

The Finglas man was arrested two months after the bombing for car theft, but all charges were dropped and he was spirited out of the republic

Last night Michael Gallagher, whose son Aidan died in Omagh, said: 'If this man has vital information on the Omagh bomb, then the PSNI should be allowed to interview him.

'There have been a number of important sources of intelligence the Garda were running who have never been allowed to be interviewed by the Omagh investigations team. It begs the question as to why this man was moved out of the republic, and where is he now?'

Henry McDonald, Ireland editor

Sunday October 5, 2003

The Observer

Families of the Omagh bomb victims challenged the Irish government last night to hand over an informer who is living abroad under a Garda witness protection programme. Relatives of those killed in the biggest atrocity of the Northern Ireland Troubles said the republic must allow detectives investigating the Real IRA murder of 29 men, women and children to interview the informant.

They were 'shocked and dismayed' that the Irish authorities had not informed the PSNI and the families that a key potential witness had been in protective custody abroad for several years.

The Observer knows the identity of the informer, who is from the Finglas area of north Dublin. At the time of the Omagh bomb he stole cars on behalf of the car dealer for the Real IRA. He knew about the plot to transport a large explosive device into Northern Ireland just prior to the massacre on 15 August, 1998. A heroin addict who fed his habit through crime, the thief told his handlers that the Real IRA planned to put a bomb in a northern town days before the blast.

The informer told his Garda contact that the Real IRA was seeking a Vauxhall Cavalier, the model used to transport the bomb to Omagh. The Real IRA asked him to approach a used car dealer in the republic for a Cavalier. When the dealer was unable to do so, the Real IRA used two other criminals, including a northerner known as 'Belfast Jim', to steal a Cavalier in Co Monaghan, 24 hours before the bombing. None of this intelligence was sent to the RUC.

'Bells should have started ringing the moment the Vauxhall was stolen, given the information the car thief had passed on to his handlers,' one Garda officer admitted yesterday.

The Finglas man was arrested two months after the bombing for car theft, but all charges were dropped and he was spirited out of the republic

Last night Michael Gallagher, whose son Aidan died in Omagh, said: 'If this man has vital information on the Omagh bomb, then the PSNI should be allowed to interview him.

'There have been a number of important sources of intelligence the Garda were running who have never been allowed to be interviewed by the Omagh investigations team. It begs the question as to why this man was moved out of the republic, and where is he now?'

Sunday Business Post

Anniversary of march into chaos

By Tom McGurk

All of 35 years ago this very afternoon, a crowd of demonstrators gathered at Duke Street in Derry.

They were relatively small in number and, apart from some nationalist politicians, including Gerry Fitt and the late Eddie McAteer, and a handful of socialist and left-wing agitators, most were what could be described as the ordinary people of Derry.

In all, a crowd of about 400 were intending to march across Craigavon Bridge and into the centre of the city.

The previous day, October 4, 1968, the then Home Affairs Minister, William Craig, had banned the march and the RUC were present in large numbers intent on enforcing his order. Among the marchers themselves there was some dispute about whether they should defy the ban, but a group led by the Derry Young Socialists would wait no longer and began to move towards the police lines.They had a blue civil rights banner and a collection of badly printed posters demanding votes, jobs, houses and fair employment.

What happened next was quite extraordinary. The RUC, who by now had sandwiched the marchers front and rear, suddenly attacked with batons and water cannon.To the astonishment of the demonstrators, who were still standing waiting to march, the police ran among them, belting people around the heads and arms. One RUC District Inspector was even wielding his blackthorn stick, the official symbol of his authority.

Something else quite extraordinary happened. In those days when television news on this side of the Atlantic consisted mainly of formal, static reporting, the RUC seemed to forget that there were cameramen present. Or perhaps, more significantly given the political climate of the times, they didn't seem to care. Among the cameramen was the late Gay O'Brien of RTE who worked calmly amid the chaos, finger on the button.

His 12-minute reel of black and white film was shown that night on RTE, and subsequently, all across the globe. O'Brien's footage was a defining moment in the coverage of the troubles and instantly established the unparalleled impact television images would play over the next decades in the North.

Because of O'Brien's images, nothing in Ireland would ever be the same again. The RTE coverage of that moment in Duke Street was like a starting pistol fired across the sleeping landscape of an Ireland then a mere two generations into partition. There could hardly have been a more articulate expression for the then state of Northern society than the casual brutality of the RUC, which was, of course, defended by the Stormont government.

Looking back,the irony is that, in the immediate years preceding the outrage in Derry, the North had actually begun to drag itself out of its one-party state torpor.

Terence O'Neill's brand of unionism had begun to melt the political ice and a generation of post eleven-plus nationalists had begun to produce a new middle class. In those rock 'n' roll years,young Catholics and Protestants had even begun to mix as never before.

Of course, the sectarian structures of the one-party unionist state were still firmly in place, but a rising tide of economic progress, education and opportunity had served for the moment to camouflage the old barriers.

That summer of '68, as discos endlessly played the Beatles' Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, there was even a sense of hope in the air. Even the Orange State, it seemed, couldn't resist the Swinging Sixties. But those violent events in Derry proved how how ephemeral all this was.

Perhaps the most ironic and subse-quently, tragic, moment of all was to come in the virulent reaction of unionism to the civil rights movement itself. If, just for a moment, unionists had stepped back and looked more carefully at what the new political phenomenon actually represented we might all have avoided the abyss that was to follow.

In realpolitik,what the civil rights movement demonstrated was that two generations into partition, there was a formidable movement among nationalists to accept the Northern state provided they could be guaranteed equal rights and status. What nationalists were demanding - at that moment anyway - was full British rights within a British state. Perhaps it was only a tactic, but it was the furthest a nationalist hand had ever reached out towards acceptance of the Six Counties as a political entity.

There is no doubt that their continuing political powerlessness in contrast to their emerging economic and educational power, was primarily responsible for this shift. With militant republicanism hibernating since the failed 1950s campaign, with their political representatives (who had actually then become the official opposition at Stormont) still left powerless and with mostly indifference, apart from rhetoric coming from Dublin, nationalism had now discovered a third, extra-parliamentary and peaceful strategy.

Tragically, mainstream political unionism, with Paisley's ranting off stage ringing in their ears, remained true to type. As the demand for civil rights was met by the resurgence of the anti-Catholic conservative evangelical tradition as represented by Paisley, mainstream unionism fell in behind.

Even O'Neill's initial steps to meet the civil rights agenda were used by unionism as weapons to destroy him.Within avery short time those nationalists who had originally withdrawn their consent from the state because it treated them as second-class citizens, and had then tried the experiment of civil rights, were once again withdrawing consent because the state had now proved itself to be unreformable. And it was into this new catharsis that militant republicans eagerly stepped.

`What ifs' are mere historical parlour games, but had that October 5 march not been banned, and had O'Neill been allowed by mainstream unionism to respond to the civil rights campaign, maybe a perilous corner might have been negotiated safely.

But such was the determining power of sectarianism within unionism, that the potential politics of the crisis was rendered invisible - simply be caus e they were Catholics. As ever, anti-Catholicism was used as a mobilisation to defend the socioeconomic and political position of Protestants and as a rationalisation to legitimise all consequent discrimination.

Those drawn police batons of October 5, 1968 - 35 years ago today - slammed shut a tiny window of opportunity that had unexpectedly opened.

comment@sbpost.ie

They were relatively small in number and, apart from some nationalist politicians, including Gerry Fitt and the late Eddie McAteer, and a handful of socialist and left-wing agitators, most were what could be described as the ordinary people of Derry.

In all, a crowd of about 400 were intending to march across Craigavon Bridge and into the centre of the city.

The previous day, October 4, 1968, the then Home Affairs Minister, William Craig, had banned the march and the RUC were present in large numbers intent on enforcing his order. Among the marchers themselves there was some dispute about whether they should defy the ban, but a group led by the Derry Young Socialists would wait no longer and began to move towards the police lines.They had a blue civil rights banner and a collection of badly printed posters demanding votes, jobs, houses and fair employment.

What happened next was quite extraordinary. The RUC, who by now had sandwiched the marchers front and rear, suddenly attacked with batons and water cannon.To the astonishment of the demonstrators, who were still standing waiting to march, the police ran among them, belting people around the heads and arms. One RUC District Inspector was even wielding his blackthorn stick, the official symbol of his authority.

Something else quite extraordinary happened. In those days when television news on this side of the Atlantic consisted mainly of formal, static reporting, the RUC seemed to forget that there were cameramen present. Or perhaps, more significantly given the political climate of the times, they didn't seem to care. Among the cameramen was the late Gay O'Brien of RTE who worked calmly amid the chaos, finger on the button.

His 12-minute reel of black and white film was shown that night on RTE, and subsequently, all across the globe. O'Brien's footage was a defining moment in the coverage of the troubles and instantly established the unparalleled impact television images would play over the next decades in the North.

Because of O'Brien's images, nothing in Ireland would ever be the same again. The RTE coverage of that moment in Duke Street was like a starting pistol fired across the sleeping landscape of an Ireland then a mere two generations into partition. There could hardly have been a more articulate expression for the then state of Northern society than the casual brutality of the RUC, which was, of course, defended by the Stormont government.

Looking back,the irony is that, in the immediate years preceding the outrage in Derry, the North had actually begun to drag itself out of its one-party state torpor.

Terence O'Neill's brand of unionism had begun to melt the political ice and a generation of post eleven-plus nationalists had begun to produce a new middle class. In those rock 'n' roll years,young Catholics and Protestants had even begun to mix as never before.

Of course, the sectarian structures of the one-party unionist state were still firmly in place, but a rising tide of economic progress, education and opportunity had served for the moment to camouflage the old barriers.

That summer of '68, as discos endlessly played the Beatles' Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, there was even a sense of hope in the air. Even the Orange State, it seemed, couldn't resist the Swinging Sixties. But those violent events in Derry proved how how ephemeral all this was.

Perhaps the most ironic and subse-quently, tragic, moment of all was to come in the virulent reaction of unionism to the civil rights movement itself. If, just for a moment, unionists had stepped back and looked more carefully at what the new political phenomenon actually represented we might all have avoided the abyss that was to follow.

In realpolitik,what the civil rights movement demonstrated was that two generations into partition, there was a formidable movement among nationalists to accept the Northern state provided they could be guaranteed equal rights and status. What nationalists were demanding - at that moment anyway - was full British rights within a British state. Perhaps it was only a tactic, but it was the furthest a nationalist hand had ever reached out towards acceptance of the Six Counties as a political entity.

There is no doubt that their continuing political powerlessness in contrast to their emerging economic and educational power, was primarily responsible for this shift. With militant republicanism hibernating since the failed 1950s campaign, with their political representatives (who had actually then become the official opposition at Stormont) still left powerless and with mostly indifference, apart from rhetoric coming from Dublin, nationalism had now discovered a third, extra-parliamentary and peaceful strategy.

Tragically, mainstream political unionism, with Paisley's ranting off stage ringing in their ears, remained true to type. As the demand for civil rights was met by the resurgence of the anti-Catholic conservative evangelical tradition as represented by Paisley, mainstream unionism fell in behind.

Even O'Neill's initial steps to meet the civil rights agenda were used by unionism as weapons to destroy him.Within avery short time those nationalists who had originally withdrawn their consent from the state because it treated them as second-class citizens, and had then tried the experiment of civil rights, were once again withdrawing consent because the state had now proved itself to be unreformable. And it was into this new catharsis that militant republicans eagerly stepped.

`What ifs' are mere historical parlour games, but had that October 5 march not been banned, and had O'Neill been allowed by mainstream unionism to respond to the civil rights campaign, maybe a perilous corner might have been negotiated safely.

But such was the determining power of sectarianism within unionism, that the potential politics of the crisis was rendered invisible - simply be caus e they were Catholics. As ever, anti-Catholicism was used as a mobilisation to defend the socioeconomic and political position of Protestants and as a rationalisation to legitimise all consequent discrimination.

Those drawn police batons of October 5, 1968 - 35 years ago today - slammed shut a tiny window of opportunity that had unexpectedly opened.

comment@sbpost.ie

Anniversary of march into chaos

By Tom McGurk

All of 35 years ago this very afternoon, a crowd of demonstrators gathered at Duke Street in Derry.

They were relatively small in number and, apart from some nationalist politicians, including Gerry Fitt and the late Eddie McAteer, and a handful of socialist and left-wing agitators, most were what could be described as the ordinary people of Derry.

In all, a crowd of about 400 were intending to march across Craigavon Bridge and into the centre of the city.

The previous day, October 4, 1968, the then Home Affairs Minister, William Craig, had banned the march and the RUC were present in large numbers intent on enforcing his order. Among the marchers themselves there was some dispute about whether they should defy the ban, but a group led by the Derry Young Socialists would wait no longer and began to move towards the police lines.They had a blue civil rights banner and a collection of badly printed posters demanding votes, jobs, houses and fair employment.

What happened next was quite extraordinary. The RUC, who by now had sandwiched the marchers front and rear, suddenly attacked with batons and water cannon.To the astonishment of the demonstrators, who were still standing waiting to march, the police ran among them, belting people around the heads and arms. One RUC District Inspector was even wielding his blackthorn stick, the official symbol of his authority.

Something else quite extraordinary happened. In those days when television news on this side of the Atlantic consisted mainly of formal, static reporting, the RUC seemed to forget that there were cameramen present. Or perhaps, more significantly given the political climate of the times, they didn't seem to care. Among the cameramen was the late Gay O'Brien of RTE who worked calmly amid the chaos, finger on the button.

His 12-minute reel of black and white film was shown that night on RTE, and subsequently, all across the globe. O'Brien's footage was a defining moment in the coverage of the troubles and instantly established the unparalleled impact television images would play over the next decades in the North.

Because of O'Brien's images, nothing in Ireland would ever be the same again. The RTE coverage of that moment in Duke Street was like a starting pistol fired across the sleeping landscape of an Ireland then a mere two generations into partition. There could hardly have been a more articulate expression for the then state of Northern society than the casual brutality of the RUC, which was, of course, defended by the Stormont government.

Looking back,the irony is that, in the immediate years preceding the outrage in Derry, the North had actually begun to drag itself out of its one-party state torpor.

Terence O'Neill's brand of unionism had begun to melt the political ice and a generation of post eleven-plus nationalists had begun to produce a new middle class. In those rock 'n' roll years,young Catholics and Protestants had even begun to mix as never before.

Of course, the sectarian structures of the one-party unionist state were still firmly in place, but a rising tide of economic progress, education and opportunity had served for the moment to camouflage the old barriers.

That summer of '68, as discos endlessly played the Beatles' Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, there was even a sense of hope in the air. Even the Orange State, it seemed, couldn't resist the Swinging Sixties. But those violent events in Derry proved how how ephemeral all this was.

Perhaps the most ironic and subse-quently, tragic, moment of all was to come in the virulent reaction of unionism to the civil rights movement itself. If, just for a moment, unionists had stepped back and looked more carefully at what the new political phenomenon actually represented we might all have avoided the abyss that was to follow.

In realpolitik,what the civil rights movement demonstrated was that two generations into partition, there was a formidable movement among nationalists to accept the Northern state provided they could be guaranteed equal rights and status. What nationalists were demanding - at that moment anyway - was full British rights within a British state. Perhaps it was only a tactic, but it was the furthest a nationalist hand had ever reached out towards acceptance of the Six Counties as a political entity.

There is no doubt that their continuing political powerlessness in contrast to their emerging economic and educational power, was primarily responsible for this shift. With militant republicanism hibernating since the failed 1950s campaign, with their political representatives (who had actually then become the official opposition at Stormont) still left powerless and with mostly indifference, apart from rhetoric coming from Dublin, nationalism had now discovered a third, extra-parliamentary and peaceful strategy.

Tragically, mainstream political unionism, with Paisley's ranting off stage ringing in their ears, remained true to type. As the demand for civil rights was met by the resurgence of the anti-Catholic conservative evangelical tradition as represented by Paisley, mainstream unionism fell in behind.

Even O'Neill's initial steps to meet the civil rights agenda were used by unionism as weapons to destroy him.Within avery short time those nationalists who had originally withdrawn their consent from the state because it treated them as second-class citizens, and had then tried the experiment of civil rights, were once again withdrawing consent because the state had now proved itself to be unreformable. And it was into this new catharsis that militant republicans eagerly stepped.

`What ifs' are mere historical parlour games, but had that October 5 march not been banned, and had O'Neill been allowed by mainstream unionism to respond to the civil rights campaign, maybe a perilous corner might have been negotiated safely.

But such was the determining power of sectarianism within unionism, that the potential politics of the crisis was rendered invisible - simply be caus e they were Catholics. As ever, anti-Catholicism was used as a mobilisation to defend the socioeconomic and political position of Protestants and as a rationalisation to legitimise all consequent discrimination.

Those drawn police batons of October 5, 1968 - 35 years ago today - slammed shut a tiny window of opportunity that had unexpectedly opened.

comment@sbpost.ie

They were relatively small in number and, apart from some nationalist politicians, including Gerry Fitt and the late Eddie McAteer, and a handful of socialist and left-wing agitators, most were what could be described as the ordinary people of Derry.

In all, a crowd of about 400 were intending to march across Craigavon Bridge and into the centre of the city.

The previous day, October 4, 1968, the then Home Affairs Minister, William Craig, had banned the march and the RUC were present in large numbers intent on enforcing his order. Among the marchers themselves there was some dispute about whether they should defy the ban, but a group led by the Derry Young Socialists would wait no longer and began to move towards the police lines.They had a blue civil rights banner and a collection of badly printed posters demanding votes, jobs, houses and fair employment.

What happened next was quite extraordinary. The RUC, who by now had sandwiched the marchers front and rear, suddenly attacked with batons and water cannon.To the astonishment of the demonstrators, who were still standing waiting to march, the police ran among them, belting people around the heads and arms. One RUC District Inspector was even wielding his blackthorn stick, the official symbol of his authority.

Something else quite extraordinary happened. In those days when television news on this side of the Atlantic consisted mainly of formal, static reporting, the RUC seemed to forget that there were cameramen present. Or perhaps, more significantly given the political climate of the times, they didn't seem to care. Among the cameramen was the late Gay O'Brien of RTE who worked calmly amid the chaos, finger on the button.

His 12-minute reel of black and white film was shown that night on RTE, and subsequently, all across the globe. O'Brien's footage was a defining moment in the coverage of the troubles and instantly established the unparalleled impact television images would play over the next decades in the North.

Because of O'Brien's images, nothing in Ireland would ever be the same again. The RTE coverage of that moment in Duke Street was like a starting pistol fired across the sleeping landscape of an Ireland then a mere two generations into partition. There could hardly have been a more articulate expression for the then state of Northern society than the casual brutality of the RUC, which was, of course, defended by the Stormont government.

Looking back,the irony is that, in the immediate years preceding the outrage in Derry, the North had actually begun to drag itself out of its one-party state torpor.

Terence O'Neill's brand of unionism had begun to melt the political ice and a generation of post eleven-plus nationalists had begun to produce a new middle class. In those rock 'n' roll years,young Catholics and Protestants had even begun to mix as never before.

Of course, the sectarian structures of the one-party unionist state were still firmly in place, but a rising tide of economic progress, education and opportunity had served for the moment to camouflage the old barriers.

That summer of '68, as discos endlessly played the Beatles' Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, there was even a sense of hope in the air. Even the Orange State, it seemed, couldn't resist the Swinging Sixties. But those violent events in Derry proved how how ephemeral all this was.

Perhaps the most ironic and subse-quently, tragic, moment of all was to come in the virulent reaction of unionism to the civil rights movement itself. If, just for a moment, unionists had stepped back and looked more carefully at what the new political phenomenon actually represented we might all have avoided the abyss that was to follow.

In realpolitik,what the civil rights movement demonstrated was that two generations into partition, there was a formidable movement among nationalists to accept the Northern state provided they could be guaranteed equal rights and status. What nationalists were demanding - at that moment anyway - was full British rights within a British state. Perhaps it was only a tactic, but it was the furthest a nationalist hand had ever reached out towards acceptance of the Six Counties as a political entity.

There is no doubt that their continuing political powerlessness in contrast to their emerging economic and educational power, was primarily responsible for this shift. With militant republicanism hibernating since the failed 1950s campaign, with their political representatives (who had actually then become the official opposition at Stormont) still left powerless and with mostly indifference, apart from rhetoric coming from Dublin, nationalism had now discovered a third, extra-parliamentary and peaceful strategy.

Tragically, mainstream political unionism, with Paisley's ranting off stage ringing in their ears, remained true to type. As the demand for civil rights was met by the resurgence of the anti-Catholic conservative evangelical tradition as represented by Paisley, mainstream unionism fell in behind.

Even O'Neill's initial steps to meet the civil rights agenda were used by unionism as weapons to destroy him.Within avery short time those nationalists who had originally withdrawn their consent from the state because it treated them as second-class citizens, and had then tried the experiment of civil rights, were once again withdrawing consent because the state had now proved itself to be unreformable. And it was into this new catharsis that militant republicans eagerly stepped.

`What ifs' are mere historical parlour games, but had that October 5 march not been banned, and had O'Neill been allowed by mainstream unionism to respond to the civil rights campaign, maybe a perilous corner might have been negotiated safely.

But such was the determining power of sectarianism within unionism, that the potential politics of the crisis was rendered invisible - simply be caus e they were Catholics. As ever, anti-Catholicism was used as a mobilisation to defend the socioeconomic and political position of Protestants and as a rationalisation to legitimise all consequent discrimination.

Those drawn police batons of October 5, 1968 - 35 years ago today - slammed shut a tiny window of opportunity that had unexpectedly opened.

comment@sbpost.ie

Arrest fears over 'dirty war' book

Stake Knife authors will risk imprisonment by detailing allegations of collusion between terrorists and security forces

Henry McDonald, Ireland editor

Sunday October 5, 2003

The Observer

A former undercover soldier pledged to ignore a threat of arrest to promote his new book on the 'dirty war' in Northern Ireland. Martin Ingram, a former member of the British Army's secretive Force Research Unit, pledged to promote the book detailing allegations of collusion between terrorists and the security forces even if it means risking imprisonment.

Ingram and his co-author, Greg Harkin, have written Stake Knife, the inside story of how agents for the British Army and RUC were able to carry out criminal acts, including murder, while working for the state.

Speaking from abroad, Ingram told The Observer that he said he was determined to promote the book in the UK, despite the threat of him being arrested for alleged breaches of the Official Secrets Act. The Ministry of Defence is considering whether to prosecute Ingram and Harkin over revelations made in Stake Knife about the secret anti-terrorist war in Ulster.

'If they want to arrest me, then they can arrest me,' he said. 'I am not running away or changing my lifestyle for them.'

The ex-army whistleblower added: 'I am not doing this for myself but rather for the public interest. In a democratic society the people should know that their security forces were allowing people serving the state to break the law up to and including murder. There are also families out there who have lost loved ones that deserve to be told that in many instances the people that killed their relatives were agents working for the British state.'

Ingram said he has been told that he may be arrested if he returns to Britain, having lived for eight years outside the UK. The former soldier spent several days in jail after giving interviews to journalists about the security forces' use of agents operating inside the IRA and loyalist terror groups. Ingram and Harkin are scheduled to join a promotional tour of the book in several UK cities next month. Their Irish publishers, O'Brien Press, have said they will print the book in the Irish Republic even if the MoD decides to slap an injunction on it in Britain and Northern Ireland.

Ingram served as an NCO for 12 years in the British Army's Intelligence Corps and six years inside the Force Research Unit.

The ex-soldier has been the source of a series of embarrassing revelations for the security forces in Northern Ireland, including the plot to kill Belfast solicitor Pat Finucane and the role of 'Stakeknife', the British Army's most prized intelligence asset inside the IRA.

Earlier this year a number of newspapers named Freddie Scappattici, the former head of the IRA's internal security department, as Stakeknife.

The allegations are strongly denied by Scappattici, who has claimed the reports have put his life in danger.

Ingram's fellow author was defiant about any threats of injunction or imprisonment. 'An arrest or injunction would be an attack on free speech, which we would resist to the end. I think any move like that would backfire on the MOD,' Harkin said last night.

Stake Knife will not only explore the alleged role of Scappattici in the deaths of IRA members accused of being informers but also the activities of the late loyalist terrorist Brian Nelson. Ingram and Harkin say Nelson had been working for the FRU as far back as the early 1980s when he prevented scores of UDA murder bids in Greater Belfast.

The authors will also claim that one of the police officers accused of setting up republicans for assassination by loyalists, known as 'Geoff', is still serving in the PSNI.

Stake Knife authors will risk imprisonment by detailing allegations of collusion between terrorists and security forces

Henry McDonald, Ireland editor

Sunday October 5, 2003

The Observer

A former undercover soldier pledged to ignore a threat of arrest to promote his new book on the 'dirty war' in Northern Ireland. Martin Ingram, a former member of the British Army's secretive Force Research Unit, pledged to promote the book detailing allegations of collusion between terrorists and the security forces even if it means risking imprisonment.

Ingram and his co-author, Greg Harkin, have written Stake Knife, the inside story of how agents for the British Army and RUC were able to carry out criminal acts, including murder, while working for the state.

Speaking from abroad, Ingram told The Observer that he said he was determined to promote the book in the UK, despite the threat of him being arrested for alleged breaches of the Official Secrets Act. The Ministry of Defence is considering whether to prosecute Ingram and Harkin over revelations made in Stake Knife about the secret anti-terrorist war in Ulster.

'If they want to arrest me, then they can arrest me,' he said. 'I am not running away or changing my lifestyle for them.'

The ex-army whistleblower added: 'I am not doing this for myself but rather for the public interest. In a democratic society the people should know that their security forces were allowing people serving the state to break the law up to and including murder. There are also families out there who have lost loved ones that deserve to be told that in many instances the people that killed their relatives were agents working for the British state.'

Ingram said he has been told that he may be arrested if he returns to Britain, having lived for eight years outside the UK. The former soldier spent several days in jail after giving interviews to journalists about the security forces' use of agents operating inside the IRA and loyalist terror groups. Ingram and Harkin are scheduled to join a promotional tour of the book in several UK cities next month. Their Irish publishers, O'Brien Press, have said they will print the book in the Irish Republic even if the MoD decides to slap an injunction on it in Britain and Northern Ireland.

Ingram served as an NCO for 12 years in the British Army's Intelligence Corps and six years inside the Force Research Unit.

The ex-soldier has been the source of a series of embarrassing revelations for the security forces in Northern Ireland, including the plot to kill Belfast solicitor Pat Finucane and the role of 'Stakeknife', the British Army's most prized intelligence asset inside the IRA.

Earlier this year a number of newspapers named Freddie Scappattici, the former head of the IRA's internal security department, as Stakeknife.

The allegations are strongly denied by Scappattici, who has claimed the reports have put his life in danger.

Ingram's fellow author was defiant about any threats of injunction or imprisonment. 'An arrest or injunction would be an attack on free speech, which we would resist to the end. I think any move like that would backfire on the MOD,' Harkin said last night.

Stake Knife will not only explore the alleged role of Scappattici in the deaths of IRA members accused of being informers but also the activities of the late loyalist terrorist Brian Nelson. Ingram and Harkin say Nelson had been working for the FRU as far back as the early 1980s when he prevented scores of UDA murder bids in Greater Belfast.

The authors will also claim that one of the police officers accused of setting up republicans for assassination by loyalists, known as 'Geoff', is still serving in the PSNI.

5.10.03

JIM CUSACK

THE IRA has begun to issue apologies to families of its own members who were tortured and murdered as informers following revelations that its internal security section - the notorious "nutting squad" - was headed by at least one British Army agent known as Stakeknife.

In both An Phoblacht and the west Belfast weekly newspaper, the Andersonstown News, the IRA has apologised to the families of two IRA men - one of whom was almost certainly innocent of the charges brought against him.

It is the first time the IRA has recanted in such a fashion, and republican sources say it has been coming under intense pressure in Catholic areas from families of IRA men killed for informing.

It is expected that more apologies will be issued, as the nutting squad was responsible for killing at least 47 men accused of being informants.

One of the two agents working inside the IRA internal security unit was also suspected of passing information that led to the British Army's SAS shooting dead IRA men in Belfast and Co Tyrone.

The apologies issued in the past fortnight are on behalf of two IRA men: Michael Kearney from west Belfast, who was kidnapped, tortured and shot dead in July 1979; and Anthony Braniff from Ardoyne, who was killed in September 1981.

There is strong circumstantial evidence that agents within the IRA set up both men for execution to draw attention from themselves.

Kearney was blamed for supplying information to the RUC that led to the disruption of a planned 40-bomb blitz in Belfast in early 1979.

Although he was involved in transporting bombs to the assembly point for the attack, it is now known that Kearney did not supply the information about the bombs.

Kearney was tortured and, the IRA alleged, confessed to passing information. He was found "in breach of general orders" and shot in the head.

It has now emerged that the two men in charge of the squad that tortured and killed Kearney were working for the RUC and British Army.

The other case is that of 27-year-old Anthony Braniff, who is believed to have been responsible for setting up another IRA man, Maurice Gilvarry, for execution as an informer in January 1981.

He blamed Gilvarry for tipping off the RUC about a planned IRA bomb attack in June 1978 which was intercepted by the SAS, who shot dead the three bombers.

Braniff was eventually caught after it was discovered he was receiving a weekly wage from the British Army.

However, last week the IRA issued a statement through An Phoblacht denying he was an informer and praising him in unctuous terms.

Republican sources say there has been huge resentment among the families of IRA members shot dead as informants after it emerged the internal security squad was headed by two agents. These two men - who might have been collectively, rather than individually, known as Stakeknife - were two of the most important agents ever run inside the IRA.